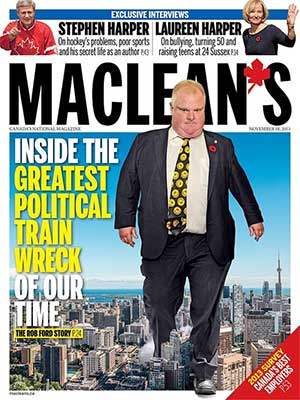

Rob Ford on the couch: Why the mayor is his own worst enemy

Originally published at Macleans.ca, November 9, 2013

Rob Ford is a complicated man, a mystery to himself and a riddle to his city. More than that: Rob Ford is engaged in a secret war against a powerful enemy he can’t see. And his war won’t end until he surrenders.

Who am I to make such claims? I’ve studied psychoanalytic theories, put in my time on the couch and spent many hours poking a flashlight into my own unconscious. The only way I can make sense of the mayor’s behavior is by putting his psyche under a microscope. Why is Ford so fascinating? Simple: Humans love drama. Drama is conflict. And Rob Ford is conflict made flesh.

Take away Ford’s self-destructiveness and he would be no more interesting than the average politician. But what makes the mayor’s saga so gripping is the mayhem he has brought on himself: alienating his allies, associating with gangsters, abusing alcohol and drugs. Rob Ford is Rob Ford’s biggest enemy. Why?

I suspect that behind Ford’s civil war stands his father. A similar relationship lay behind another tale of political turmoil: that of George W. Bush. Both the Bush and Ford sons were raised in a climate of macho one-upmanship, where they had to jostle for their dad’s scant approval. Both men are right-wing anti-intellectual populists who refuse to admit their mistakes. Both feel driven to match or exceed their fathers’ high achievements. Both sabotage themselves in the attempt and ruin their legacies.

Suede’s lyrics, “Tragic as the son of a superman”, weren’t about Rob Ford, but he might relate. Doug Ford Sr., the patriarch of the Ford dynasty, rose from poverty to found the family business and become a Tory MPP. Rob calls him his hero and seems to want to live up to his example. So he became mayor and scored a few early wins. Then the civil war heated up.

Much of what Ford has done is infamous, but what he hasn’t done is perform any of the normal functions of his office: he barely shows up for work, ignores his counterparts in other cities, spends little time formulating policies, planning, or meeting members of council, attends few public events and, when asked, is unable to think of anything he likes about Toronto.

Does he even want to be mayor?

Yes. And no. As I see it, two armies struggle for control of Ford’s psyche. The army of Ford’s conscious mind represents order, discipline, and achievement. Its flag, bearing the image of Doug Sr., flutters over the capital of his mind. This force made Rob Ford a councillor, kept him focused through a long mayoral campaign, won him a chain of office, regiments of loyal followers, and a few political battles.

But outside the capital is a steaming jungle of memory, fear and trauma: Ford’s unconscious mind. And when the guards of the capital are distracted, the insurgents come out of the undergrowth and creep over the walls. The mayor’s deeper self is pursuing a relentless, inventive and effective guerrilla war against his waking desires. The night soldiers have won many victories: Ford’s crack smoking, drunken rants, racist slurs and 911 calls from his home. But those are merely the headline grabbers. The dark forces within win subtler triumphs: on transit and budgets, Ford has repeatedly sabotaged his own plans and tainted his own victories.

None of this makes sense if you sought public office motivated by a clear sense of yourself and a deep desire to serve the city. All of it makes sense if you learned at your father’s knee that you could never be good enough. Ford is following a well-established pattern. Family therapist and author Terrence Real has written about men like the mayor: men who are “successful” by society’s standards – who built major companies, or reached the heights of their professions – yet harm themselves, their families or their legacies through addiction, destructive behaviour, self-sabotage or terrible decisions. (Many women have similar stories, but the culture tends to give men more direct access to this particular sickness.)

Real found that such men are dominated by the twin demons of grandiosity and shame. They may not consciously feel anything, but peel back the layers of their defense systems and one finds that they have an overwhelming sense of inadequacy: they see themselves as lazy or stupid or worthless. In the cases Real describes, men like this were typically taught such self-contempt by their fathers, emotionally stunted men who may have meant well but denied their sons any compassion.

So the sons grew up and their conscious minds worked like fury to clock up achievements, to help them run away from the sense of shame. The problem is that shame always runs faster.

I suspect that Ford is also running away from shame. You see it by its absence. Most other politicians would have resigned in humiliation after the least of his disgraces; Ford responds with blame, bluster, and denial. His recent apologies have been self-serving attempts to shut down all criticism while admitting nothing. He claims that he has nothing left to hide, even as he refuses to talk to the police and new scandals emerge every day.

Ford has been called shameless. I think he has shame – he’s just fighting to keep it out of his conscious mind. Like a stern preacher wearing scarlet panties under his black linen, Ford is suppressing his own nature – and loudly proclaiming the opposite.

Grandiosity, shame’s opposite, is the brittle rock on which Ford’s consciousness is built. The grandiose Ford does not compromise. He is only interested in complete victory. He is certain of the rightness of whatever he believes. This certainty won him votes. He could cut two billion from the city budget without affecting services, build subways for free, lose fifty pounds. When he fails, it’s someone else’s fault.

Why is shame exiled from Ford’s psyche? To admit to shame, to apologize, to surrender, you must make yourself vulnerable. You have to trust that others won’t kick you when you’re kneeling. If Ford would admit to his troubles, he might be repaid with support. But Ford lacks that sense of trust. He learned long ago to fear being wrong. With his father dead, his brother Doug Jr. has stepped into the role, feeding Rob a toxic mix of praise and bullying to maintain him in his worst habits. What can Ford do but keep lying and denying?

Still, the unconscious isn’t fooled. It has a single aim: to make us confront all the things we suppress. Why does Ford do what he does? Maybe because his deepest desire is to be respected on his own terms, to admit to his errors and accept forgiveness, to stop trying to live up to his father and to start learning to be himself. As long as the twin shadows of Dougs Sr. and Jr. tower over his psyche, he can’t do any of these things. So his deeper impulses are compelled to sabotage him until his conscious mind gets the message.

I sometimes like to picture the alternative careers of such men, had they been born into less burdensome families. I imagine George W. Bush as the unambitious and genial mayor of Crawford, Texas, much loved by his undemanding citizens. And Rob Ford? He would be a full-time high school football coach, helping the players with their troubles on and off the pitch, lighter and happier than the man we know.

I believe Ford could still have that life. But only if he surrenders unconditionally to his unconscious. Until then, his civil war will rage on. And the citizens of Toronto will be caught in the crossfire.